Project Detail: Groupers, the Dogs of the Sea

Contest:

Wildlife and Nature 2019

Brand:

LuganoPhotoDays

Author:

W Goodwin

Status:

Selected

Project Info

Groupers, the Dogs of the Sea

The Nassau grouper is a curious, playful apex-predator that live to more than 30 years old. These large fish (up to four feet and 55 pounds) tend to meet their food needs easily which leaves them much of the day to explore their section of the reef. Unfortunately for them, they are a very popular food fish. Consequently, Nassau groupers are over-fished and in recent decades their numbers have dwindled until they are now an endangered species throughout their range according to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature – Geneva. (Full disclosure: the IUCN voted this writer their 2011 Underwater Photographer of the Year from an international pool of candidates nominated by member scientists.) With their numbers rapidly approaching the point of no return, I became determined to call attention to their plight by illuminating, literally and figuratively, the vulnerability of the Nassau grouper, a fish that displays behavioral traits suggestive of a curious, playful dog!

This is my story of how one young Nassau grouper inspired me to show these endearing fish to the world in the hope more people will want to protect them from disappearing altogether.

The locus for my continuing study of Nassau groupers is the tiny island of Cayman Brac in the Caribbean, a place I’ve visited fifteen times in the last twelve years. During one of my first dives beneath the clear waters of this island, I was exploring Buccaneer Reef when I came upon a pair of these groupers. One was quite large, the other rather small. The big guy seemed to ignore me; he was too involved in supervising the younger one that was working on his own little project. As I watched, the smaller grouper repeatedly tried to swim through a tight little tunnel where the reef met the sand, but it was partially blocked by sand. At first the little grouper could not get through and had to back out several times. It kept trying.

Inside the slot-like tunnel, the little grouper turned on its side. Twisting and fluttering, it worked hard to enlarge the space. Under the watchful eye of the larger fish, the “kid” continued its efforts to slip through the tunnel. Clouds of sand flew from both openings of the tunnel until finally the little grouper emerged from the far end. The first thing he did was look up at me as if to say, “Yay! I did it!”

This small grouper, which I unofficially named “Slip” after that first dive, became my frequent escort and guide at Buccaneer Reef. Sometimes leading, sometimes following, he showed me around “his” reef, often pointing like a finny hunting dog at the hiding places of sneaky lionfish and surreptitious lobsters.

On my tenth day on the Brac and twenty minutes into my fourth dive at Buccaneer, as usual Slip was never out of my sight but then I lost track of him. I was about to conclude he was occupied elsewhere when I saw something odd. A large purple sea fan waved in the surge a few feet from me and peeking through a hole in the fan’s matrix was Slip. He was watching me! I took a picture and later entered it into the 2008 International Coral Reef Symposium annual photo contest for its members, marine biologists, oceanographers, marine park managers and other reef stakeholders. That image won Best in Show and was later picked up by the Cayman Islands newspapers. The accompanying article featured an interview with me in which I said this kind of grouper behavior is only observable where no-take protected zones are established. Later that same year the Caymanian government passed a law banning all spearfishing for Nassau groupers in the Cayman Islands. One of the ministers told me the image and story about that grouper were instrumental in convincing the government to pass the new law protecting Nassau groupers.

Thus encouraged, I conceived of this project to show the world that groupers, though delicious, are better protected than eaten because, in addition to other reasons, they are more valuable as a dive attraction than as an item on the menu.

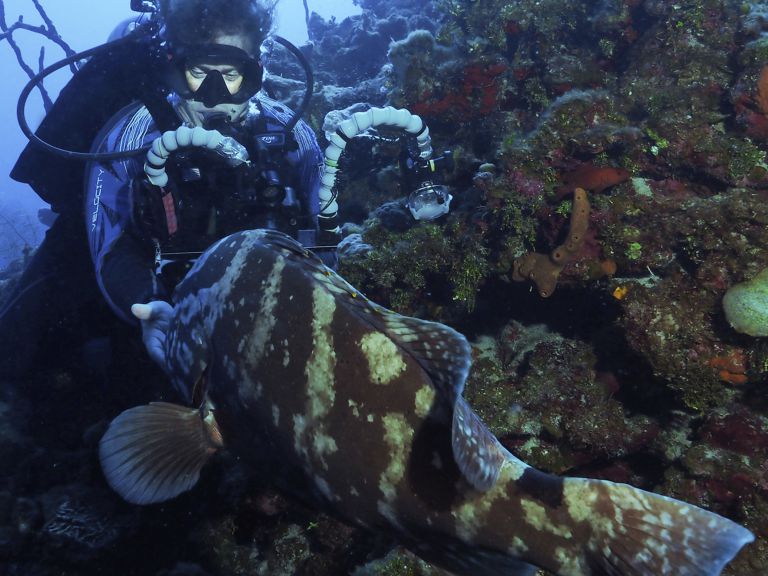

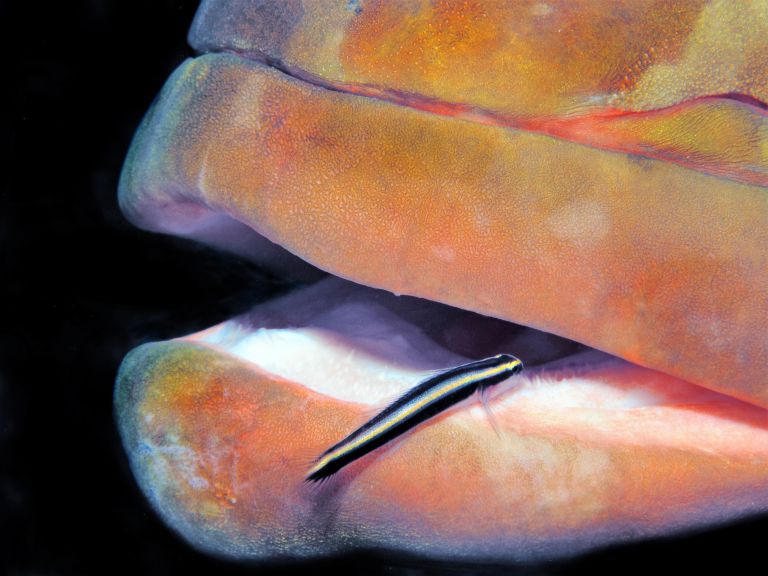

In talks and articles I often assert that Nassau groupers share behavioral characteristics with dogs. I’ve spent almost a thousand hours observing and interacting with these amazing animals, and I’ve come to feel that killing and eating them is like killing and eating collies or retrievers. Few people know the grouper they’re eating loved to be petted! My team and I have determined this has nothing to do with food or parasites – they simply love to be petted! Many people, even divers, are unaware groupers are also very vocal, and if the humans are not quick to notice them, they’ll vocalize to get our attention. When they hide too well, they’ll vocalize to show us where they are. They also play peek-a-boo. On many occasions, I’ve seen a Nassau come up behind one of my dive partners and for ten minutes swim mere inches away from the unsuspecting diver’s legs. And they love to investigate our gear, often coming right up to a diver and stare intently at a fin or regulator or camera.

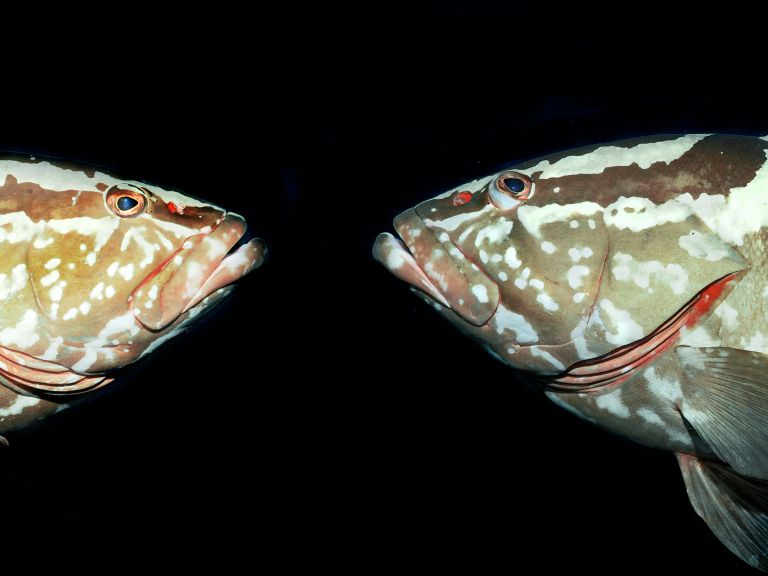

Diving in the same locale year after year has allowed me to identify half a dozen individual Nassau groupers on the Brac, at least three of which I’ve “known” for over ten years. I devised a system for differentiating between individuals by using the number and pattern of white spots on what I term the “identifier band,” the dark stripe running through each eye and passing over the nape. And of course animals with such dog-like behaviors get names. Alice. George. Slip. I’m a biologist and I know naming a wild animal is not exactly “hard” science. These groupers are no longer mere scientific subjects and they certainly should not be slaughtered for food. My project aims to demonstrate that because of their sentience as well as their dwindling and slow-to-recover populations, they desperately need protection.

I must make it very clear that during these in vivo investigations, my team and I have never resorted to baiting, chumming or other feeding to attract a grouper, nor do we ever use sound makers or other potential attractors or disrupters.

Time is running out for these magnificent fish. Their very existence is threatened by over-fishing, habitat loss, pollution, late sexual maturity, and the facts they are easy targets for all types of fishing because of their fearless curiosity and their annual “sitting-duck” mating congregations. I sincerely hope to shed some light on their predicament and raise sympathy and support for these noble animals.