Project Detail: Eleventh Night

Contest:

Reportage and Documentary 2020

Brand:

LuganoPhotoDays

Author:

Alex Zoboli

Status:

Selected

Project Info

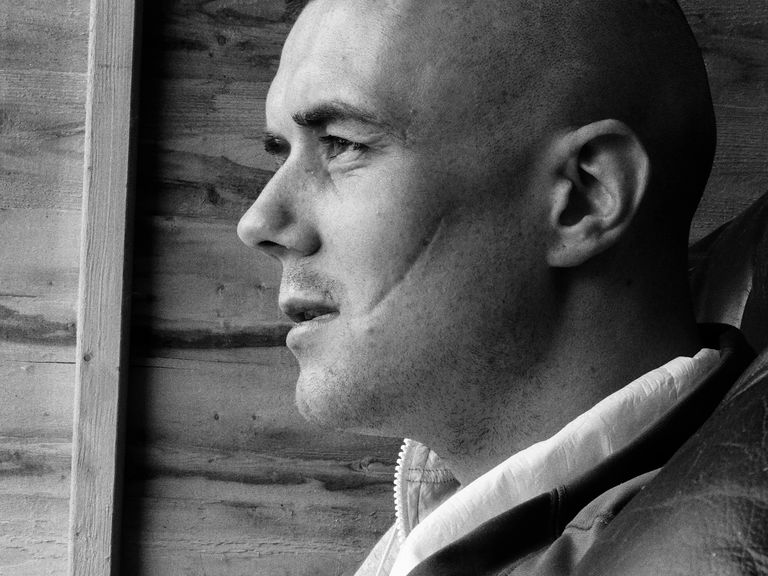

Eleventh Night

23 years ago, the good Friday agreement was signed, ensuring an end to the armed conflict that had devastated Northern Ireland for 30 years and the beginning of a precarious restoration and peace keeping process. However, the conflict’s legacy, physically embodied by the peace walls in Belfast, the sectarian festivities and through an abnormally high suicide rate linked to PTSD (placing NI in the top quarter of the international tables) and drug and alcohol abuse, still plagues both the generation directly involved in the conflict and those who have never experienced it in the first place. Since the peace agreement, a majority of the people of Northern Ireland have worked to bring communities together, heal the trauma and move towards a better future for all but, due to Brexit and the new Irish sea border between NI and England, this process is at risk of failing, threatening to plunge NI back into the sectarian violence they worked so hard to remove from the collective consciousness.

Traditionally, bonfires are lit the night before the Twelfth of July and the aim is to make them as big - and as brutal - as possible.

Over the years, for many loyalists the fires were not complete without an Irish flag, a Glasgow Celtic shirt or a Catholic emblem on the top for a ceremonial burning.

It costs thousands of pounds every year to clean up the mess the fires create across Northern Ireland. It is not just a tidy-up operation - in some cases burnt roads have to be re-surfaced.

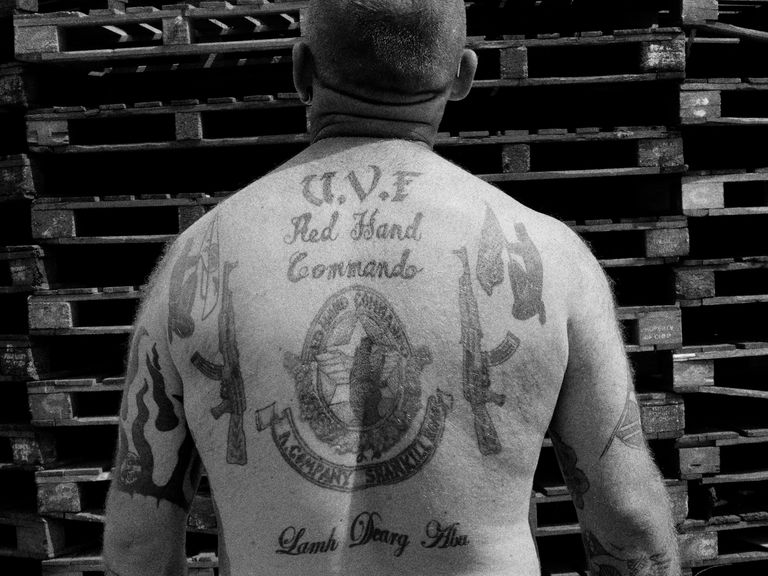

In the past, there have been so-called 'shows of strength' by the UDA and UVF at some bonfires, when hooded gunmen appeared from the shadows and fired bullets into the night air to whoops of delight from a cheering, drunken crowd.

The following day, the streets of Ulster are flooded with large parades, held by the Orange Order and Ulster loyalist marching bands, streets are bedecked with British flags and bunting.

Orange marches through Irish Catholic and Irish nationalist neighbourhoods are usually met with opposition from residents, and this sometimes leads to violence. Many people see these marches as sectarian, triumphalist, supremacist, and an assertion of British and Ulster Protestant dominance. The political aspects have caused further tension. Marchers insist that they have the right to celebrate their culture and walk on public streets, particularly along their 'traditional routes'.