Project Detail: Belfast: Being Young in a Divided City

Contest:

Reportage and Documentary 2019

Brand:

LuganoPhotoDays

Author:

Marika Dee

Project Info

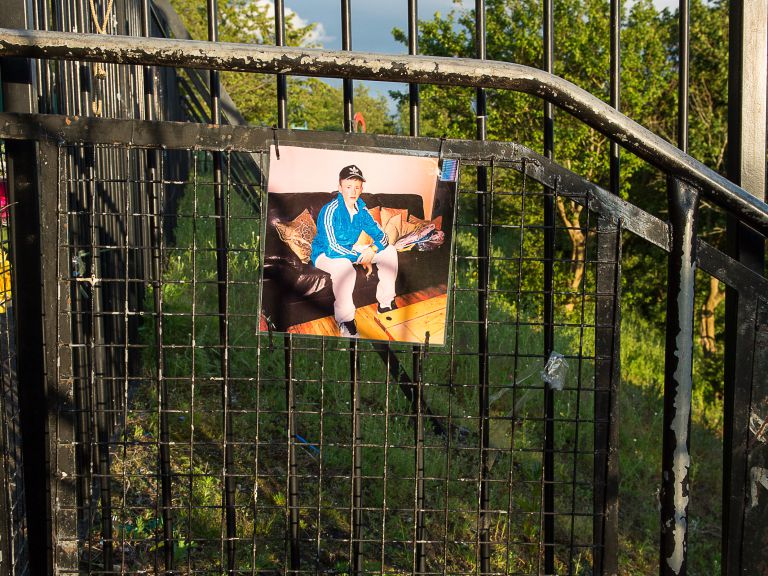

Belfast: Being Young in a Divided City

The working-class areas of Northern Ireland's capital Belfast witnessed some of the worst violence during the three-decade-long conflict between the mostly Catholic republicans who wanted a united Ireland and the mostly Protestant loyalists who wanted to remain part of the UK. Most young people growing up in these economically and socially deprived areas have not experienced the Troubles firsthand — the violent conflict ended over twenty years ago with the Good Friday Agreement — yet their lives continue to be shaped by its ongoing legacy. The city's working-class areas are still divided along sectarian lines and their Catholic and Protestant communities lead largely segregated lives. Young people grow up in a deeply divided society with an entrenched us-versus-them mentality. They live in a risk-laden environment and are exposed to poverty, barriers and paramilitaries.

Once the scene of intense violence, Belfast city center has been re-imaged as a place of normality. This new consumer-oriented Belfast with its up-market bars and shops has no place for visible traces of the violent past.

But although not far in distance, the city's working-class areas are a world apart. The legacy of the Troubles continues to cast a long shadow in these areas that witnessed some of the worst violence during the three-decade-long conflict between the mostly Catholic republicans who wanted be part of a united Ireland and the mostly Protestant loyalists who wanted to remain part of the United Kingdom. More than 3500 people were killed during the Troubles, many of them in the working-class areas of Belfast.

Most young people growing up in these areas have not experienced the Troubles firsthand — the violent conflict ended over twenty years ago with the 1998 Good Friday Agreement — yet their lives continue to be shaped by its ongoing legacy. The city's working-class areas are still divided along sectarian lines and their Catholic and Protestant communities lead largely segregated lives. Working-class youth are growing up in a deeply divided society with an entrenched us-versus-them mentality.

Physical barriers, the so-called peace walls — a palatable euphemism for segregation barriers — are the most visible reminder of Northern Ireland's conflict. The peace walls separate the Protestant and Catholic communities and were built to reduce violence. But not all spatial barriers are physical, many are psychological, invisible dividing lines used by local people to structure their basic daily routines and practices. People construct mental maps in which space is labeled as "ours", "theirs" or "neutral".

Sectarian divisions in housing, schooling, sports and social life leave few opportunities to meet youth from the other community, making it hard to have real friends across the divide.

Segregation is not the only post-conflict reality young people have to deal with. Paramilitary groups that were active during the conflict retain a grip on their communities. These groups have evolved into criminal organizations engaged in drug trafficking, protection rackets and other criminal activities. The paramilitary groups continue to recruit young people often through coercion or in payment for drug debts.

Young people face numerous challenges and poor prospects. The working-class areas, the worst affected during the conflict, are among the most economically and socially deprived in the UK. Unlike the city center, these areas have not benefited from the promised peace dividend and have lost out economically. Rampant youth unemployment leaves many young people with low aspirations. Poverty is widespread, academic achievement is low and drug and alcohol abuse among young people has increased. Mental health is problematic and the suicide rate, particular among young males, is one of the highest in Western Europe.